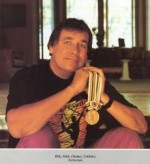

Record-holding runner visits campus

With 300 meters left in the 1964 Tokyo Olympic10 km race, United States runner Billy Mills is in third place. Ron Clarke from Australia, who held the world record at the time, pushes him and he stumbles.Exhausted, Mills runs into the final corner to face the last 100 meters. A German being lapped moves to lane five opening lane four.

“Just one more try,” he said to himself.

While running by, Mills sees an eagle in the center of the German’s jersey and remembers what his father told him.

“‘Son you have broken wings,'” Mills recalled his dad saying to him while on a fishing trip just a month after his mother’s death.

His dad draws a circle in the dirt with a stick and tells then 9-year-old Mills to step inside, close his eyes and look deep inside of his heart, body and soul. His father claps his hands and asks Mills what he saw. Mills is speechless.

His father said he found anger that his mother died, hate because of how Native Americans are treated, jealousy that “‘blinds you so you don’t see virtues in our culture,'” and self-pity. “‘All those emotions will destroy you,'” he told his son. “‘It is the pursuit of a dream that heals you.'”

Mills remembered on that last stretch of the race his father telling him to look beyond his emotions to “‘find that dream and passion to take you down the path of destiny. Have wings of an Eagle.'”

The eagle on the German’s jersey gave Mills wings and the strength to fly.

He became the first and only American to ever win the gold in the 10 km with a world record time of 28:24.4, which still stands today.

“When the moment was delivered it was a gift from my creator,” Mills said last week in a telephone interview, explaining that he did all of the work and training — but the win, the gold, was a gift.

When Mills finished, a Japanese official grabbed him and said, “Who are you?” Mills said. Mills could not comprehend what he was saying and initially thought he miscounted laps and still had one more to go.

Mills said that when his father told him to look deep within to find positive desires, he also said he hoped his son would try sports. At age 12, Mills’ father died and he was sent off to boarding school, which led to breaking high school track records, an athletic scholarship to the University of Kansas, and to the U.S. Marine Corps where he trained for the Olympics.

Mills said that by being an athlete, he felt he was communicating with this dad. It was “the way of feeling he is with me,” Mills said. He tried boxing, basketball, and football before realizing running was his true desire. Mills then recalled the first book he remembers reading was about the Olympics, making him want to be an Olympian.

But the pursuit wasn’t easy.

Even when he made the team, the U.S. Olympic Committee didn’t have enough shoes for the whole team and gave shoes only to the runners expected to do well.

Mills was not one of them. He ran in borrowed shoes.

“Here’s a man that wasn’t expected to finish in the top half of that race, but ended up running a career-best by almost 50 seconds on the largest stage for any athlete, even without the support of his own coach,” said Castleton cross country runner, Chris Gatchell, who said he’s excited that Mills is coming to Castleton. He said many athletes limit themselves and don’t push themselves beyond those limits like Mills did.

“I hope that teams and other students can really get an appreciation for what Billy Mills signifies,” he said. “My hope is that Billy’s story allows some athletes and students to stop letting limitations get in the way.”

Dr. Lara Carlson, exercise science coordinator and professor in the department of natural sciences at Castleton State College, is the woman behind Mills’ visit as the keynote Soundings speaker this year. She first met Mills as a graduate student and assistant track coach at the University of South Dakota.

The head track coach had Mills come to speak with the team and that’s where Carlson got to ask Mills about training and staying motivated in highly competitive situations.

“To meet someone who has persevered .” Carlson said trailing off almost in awe. “He does a lot for the Sioux and Native Americans in South Dakota.”

She explained how Mills founded and is spokesperson for Running Strong for American Indian Youth, a group devoted to helping young runners find their dreams.

But Mills talks more about finding a life of peace and happiness than about running in his book Wokini, renamed Lessons of Lakota.

He was born on Pine Ridge reservation in South Dakota, which is one of the poorest communities in America with unemployment around 80 percent.

“The reservation is rich in culture and spirit,” said Mills, when asked about his upbringing.

He stressed that the gold medal was not a ticket out of the terrible living conditions on the reservation, but the way he acquired the opportunity to gain a college education, to travel, and educate others.

“Because of sports, I can go all over the world,” he said, saying the medal created exposure and the means to educate people on Native American issues and promote change through critical thinking programs.

Mills said his running ability placed him in a unique position to be an activist and encourage global unity, because he says it is the key to the future of mankind. Mills’ message echoes what he learned about life though sports; to have a vision, a mission and values, which are always sacred.

“It feels like he radiates passion for life and genuine passion for all humanity,” Carlson said of Mills. “Even if you are not a runner, how can you not appreciate?”

Carlson recalls a scene from the movie ‘Running Brave’ about Mills’ life before winning the gold, when he returned home to the reservation to remind himself why he runs and the need to find that internal motivation.

“External things make you forget why you’re doing it,” Carlson said.

“His story is such a tale of the underdog,” she said, in front of a computer with the famous photograph of Mills’ gold medal win as her desktop. “It’s not fiction; it’s true.