A Q&A with Lily Doton

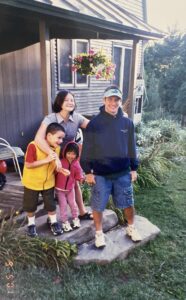

Lily Doton is Media and Communication major at Castleton University. She was born in Korea, and was adopted by a family of Vermonters from Barnard when she was a baby. The 22-year-old just started writing seriously this past semester, and finds comfort in sharing her stories. She is passionate about social justice and equality, and seeing Asian people on screen whether that’s in movies, shows or through music.

Q. What was your initial reaction to the Atlanta shooting?

A. “I don’t know how to explain it really, because it wasn’t shock, I just kind of like froze for a second. I found out on Twitter, and I was having like an okay day, and then all of a sudden I couldn’t do anything for a while.”

Q. What are your thoughts now?

A. “Honestly, I kind of stayed like that for a couple days where I was just functioning on a very low level, doing everything that I had to do but not really doing anything beyond that. Now I’m kind of, honestly I don’t know. After I wrote that piece, it was really cathartic for me so I feel like I got out a lot of those feelings that I was having. Now I’m just kind of looking for things that I can do to prevent this from happening, to keep myself safe, to help keep others be safe in whatever way I can, seeking out organizations and people who are speaking out about these things.”

Q. How has Asian hate increased in the past few years?

A. “Growing up in Vermont, I feel like I didn’t really know that much about what was going on before, before I started being more politically involved or politically aware, which wasn’t really until my senior year of high school. I think for a lot of Asian people, before it was mostly just microaggressions and little comments and things like that, and I think that’s gotten worse, and now with the addition of violence too. I think that is something that hasn’t been widely seen in a long time. Honestly, we didn’t learn that much about what it was like for Asian people in America, like I took AP U.S. History and we didn’t talk about it. I think that Donald Trump’s comments have definitely exasperated all of these things, I mean he was calling (coronavirus) the Kung Flu, the Chinese virus, I mean there’s no way that those things didn’t have an impact, coming from a president. Not that it’s the cause, but it definitely didn’t help.”

Q. If you don’t mind sharing, and you touched on this a little bit, but what has been your experience as an Asian American in Vermont?

A. Mostly comments, like I said, a few worse than others. For the most part it’s little jokes that I used to take part in in high school. Because I didn’t know how to be Asian without making it into a joke, at the time. As I got older, I started noticing comments from men, mostly. I worked at a restaurant, and there were a couple instances where I got comments from older men.”

Q. What kind of comments, if you don’t mind sharing?

A. “This one guy, he and his friends and their wives came in, and I was their server. And they asked me, of course, ‘where are you from?’ and I said ‘Woodstock, Vermont,’ and they were like asking me about my heritage, so I told them I was Korean, and then every time I came back to the table, he would speak to me in really butchered Korean, even though I told him I don’t speak Korean, I can only say ‘hi,’ basically. He told me that he lived in Korea for a little bit, he and his wife, and I was like okay that explains why he was doing that, whatever. Then he was like, ‘our biggest regret is not bringing a Lily home.’ I think I must’ve told him I was adopted, but I was like… that’s so weird. And then one of the other ladies, I can’t remember if it was his wife, was like ‘it’s not too late, what are you doing tonight?’

Q. What are your thoughts about the public’s reaction to not just the shooting, but also toward Asian hate, with the uprise of the hashtag #stopasianhate?

A. “I’m glad to see that it’s gaining some traction, because I feel like for so long Asian people have been invisible in a way. So, I’m really glad people are talking about this now, and sharing places to donate, and just being more active than I think they would have been in the past. One thing that is really frustrating me, though, is I’m seeing a lot of this being targeted at Black people, basically saying they need to be the ones to step up to help Asian people. I just think that is part of this whole thing that like, supports white supremacy, pinning groups of people of color against each other, saying that this other group is the cause of your problems, not white people. Like you should focus on this other group, and when you both fix it then it will be okay, which is kind of taking white people out of that equation. And I have seen like a fair amount of that. I think that there should be support among communities, but it shouldn’t all fall on people of color help each other and support each other.”

Q. What do you think white people need to realize when it comes to Asian hate?

A. “When it comes specifically to Asian hate, I think one issue is that we’re still seen as the model minority. Other stories of Asian people not doing well financially, which is the thing that sets Asian people against other groups of color, supposedly, but of course there are Asian people who aren’t doing well financially. I remember learning about this briefly, part of what separates that is a lot of Asian households make more money because there are more adults in the household, like more family members. I just feel like when white people view all Asian people as a monolith, seeing Asian people, first of all, as being only East Asian, only light-skinned East Asian, seeing all Asian people as being smart and wealthy, and doing well. When you see those things it kind of erases any kind of struggles Asian people have had. I think it’s important to acknowledge that there is that disparity among Asian people and other people of color as a whole, I just think that there’s a real problem with viewing all Asian people as the same.”

Q. Asian culture has become such a big part of American culture – there’s a discourse happening between people who think you should speak up because it’s the right thing to do, and other people who think if you take any part in Asian culture then you need to speak up. What do you think about this conversation?

A. “I definitely think that that’s true. If you take enjoyment or your favorite artists are Asian, then why would you not want to talk about this issue? It just doesn’t make sense to me, because if you love these people, and they are Asian, wouldn’t you want to support other people that are like them? I feel like the same conversations were happening with BLM, like if you listen to rap music, then you should be involved in this conversation. I think taking little things from Asian cultures is so common, even among western artists. Like don’t get me wrong I love Ariana Grande and Nicki Minaj, but there have been issues with both of them with Nicki and Chun Li, like her stage decoration for that was a mix of Chinese, Japanese and Korean costumes and architecture. That just makes it clear that you’re not respecting that culture.”

Q. Do you remember Gwen Stefani and her Harajuku Girl era?

A. When there’s so few images of Asian people in the media, and the ones that you are getting are Harajuku Girls or quiet little Geisha girls, when those are your only representations … (trails off without finishing the thought).

Q. Microaggressions and stereotyping have become something that we don’t recognize but has become so normalized in Western media, how do you think we can prevent that from happening more and more?

A. “That’s a big question. To go a little off topic, I’m taking Black American Cinema with Professor Michael Talbott this semester, and the thing that he always presses is that representation matters, moving pictures matters. The things that we see in all different forms of media, truly then form what we think, even if we don’t realize that. So I think a big thing of that is seeing Asian stories on screen, in authentic ways, like we don’t always need to be the nerdy side character or the guy that works in I.T, or the person that speaks broken English and works in a convenience store, that’s not true to all Asian American experiences, and it’s kind of seen as if it is. I think it’s important to show Asian people in different roles, in different kinds of media.

Q. What do you think about [the suspect] shooting Asian woman because they are the cause of his sex addiction?

A. “I think it goes back to the fetishization of Asian woman, how they are seen as docile, as sex objects. I doubt there is one Asian woman that hasn’t gotten a comment about something like that, just because she’s Asian. I think the assumption is that Asian women are all submissive and just inherently sexual. I think it of course has to do with just women in general, but I think there is a really specific thing when it comes to Asian women, especially Asian women working in spas and stuff. They are the ones who are most vulnerable and seen in that way.”

Q. Is there anything else you want to say?

A. “I guess just that I want people to listen to Asian people when they talk about this. I mean it sounds so simple because it is. Rather than talking over someone, just try to listen. I think it’s really easy to pass it off as a sex addiction, but if you peel back the layers and look at it, why is it that six Asian women are the first thing you think of when you’re like ‘this is the fuel of my sex addiction.’ What systems do we have set up to make him think that?”